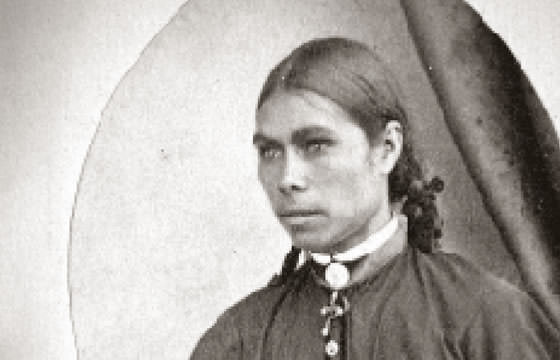

W hen the government decided to set up a telegraph station at the New Norcia (Western Australia) mission, they asked Bishop Salvado, its founder, if he could recommend anyone. The bishop thought he knew just the right person. She was Helen Pangerian Cuper, a tall, handsome woman with long black hair, who was already in charge of the post office.

hen the government decided to set up a telegraph station at the New Norcia (Western Australia) mission, they asked Bishop Salvado, its founder, if he could recommend anyone. The bishop thought he knew just the right person. She was Helen Pangerian Cuper, a tall, handsome woman with long black hair, who was already in charge of the post office.

Born in Bunbury of an Aboriginal mother and a European father, Helen had come to New Norcia a few years earlier and married a local Aboriginal farmer. Her work with the postal service was satisfactory but could she handle the techniques of telegraphy? Salvado got hold of a book and taught himself Morse code, which he then taught to Helen. When the telegraph superintendent visited New Norcia to check on progress, he was surprised to find the intended telegraphist was an Aboriginal woman. ‘You need a good musical ear,’ he told the bishop, ‘a good telegraphist reads more with the ear rather than the eye, transcribing the telegrams without seeing them.’

So the superintendent gave her a test, writing two long messages in telegraphic signs for her to read. Which she did swiftly, to his satisfaction. Then he gave a telegraphic key, so that she could learn to send messages. He warned that Europeans sometimes failed to master the technique even after six months. Two days later he was back and was surprised to find Helen already an efficient telegraphist. Thus Helen Pangerian Cuper became the first Aboriginal telegraphist in Australian history.

Her first telegram, sent on 4 March 1874, was to the governor in Perth, thanking him for the appointment. Replying, the governor commented on her telegraphic skills. Not everyone was convinced. They said that someone else was sending the telegrams, not ‘a half-caste Aborigine’ as the local paper described Helen. In time, however, she proved them wrong: the New Norcia ‘hand’ was always the same, there were no variations whatever time of day the operator worked. Later, the postmaster-general told Salvado that Helen was the best telegraphist in WA.

Elegant handwriting was another feature of Helen’s skill-set, because as postmistress she had to keep detailed registers – mail in and out, local or overseas, registered or insured. Her duties as official telegraphist were more demanding: records of time and date of each telegram; its origin (government department, commercial, legal, church, police or medical); paid or unpaid; and its precise number of words. Monthly returns on all these had to be accurate. The job required superior book-keeping abilities, which she demonstrably had.

She did not keep her job for long because she was afflicted with tuberculosis, a deadly disease in the 19th century. Two or three tubercular episodes convinced her to leave New Norcia and seek medical care in Perth. Before she left, she and Salvado picked a replacement whom they trained together. This was Sarah Ninak, a ‘full-blood’ Aborigine. She proved to be as adept at telegraphy as Helen had been, which shut the mouths of mean people who said that Helen’s expertise had come from the European side of her genetic makeup.

A test of this came when a new governor visited New Norcia. He went to the telegraph office and asked Sarah to send a telegram to Perth. While he and his wife were talking to her, Sarah deftly sent off his telegram. Salvado saw what was happening and feared that the young woman would be distracted and make mistakes. No need to worry: she sent the telegram easily and followed this with other demonstrations of her skill.

The governor spent three hours in Sarah’s office and later spoke warmly of her ability, showing friends examples of her handwriting, which was as elegant as Helen Cuper’s. He asked the bishop for a photograph of the telegraphist to send to London. In an accompanying letter to the Minister for the Colonies he praised both Helen and Sarah. They showed Salvado’s success in working with Aborigines and what they could achieve in the new society of WA.

We know about the Aboriginal telegraphists from Bishop Salvado’s lengthy 1883 report to the Vatican, recently translated by Brisbane academic Stefano Girola (published by Abbey Press, Northcote, Victoria). Salvado had quietly trained another Aboriginal woman as telegraphist, Carmen Gnarbak, a teenager who proved the equal of the other two. When the tubercular Helen Cuper died, in 1877 aged 30, however, her replacements took fright and resigned. Still Salvado’s pride in their achievements shines through his 1883 report.