The religious Christian art is a reflection of our belief and understanding of its mysteries, an attempt to not only convey but also to get a step closer to the divine. It inspires and invigorates the viewer offering an interaction and further contemplation about the complexity of the mysteries.

The religious Christian art is a reflection of our belief and understanding of its mysteries, an attempt to not only convey but also to get a step closer to the divine. It inspires and invigorates the viewer offering an interaction and further contemplation about the complexity of the mysteries.

The power of spoken word as well as music is undeniable and immense, albeit ephemeral while an artwork is there for all time inviting to be seen again with a fresh eye according our own spiritual growth and better understanding of art itself. The communication can never be one-way, a viewer needs to do the necessary work on both accounts as so much can be misleading and misunderstood unless the grasp of the matter is attained.

This text can touch the topic but in a most rudimentary way given the complexity of the subject and space to condense it in. How is the feast of feasts in the Christian calendar depicted, how can a mystery of faith be brought forward, how can the invisible be made visible...?

UNDERSTANDING ICONS

To begin with, we ought to make a distinction between the religious art and icons as the two are far too easily confounded and taken as one and the same. As with so many things, the original notion of the icon has mutated and came to signify symbols, things and people of (utter) reverence and respect, thus our vernaculars had adopted this word which became so much used that it finished by being abused.

While the West uses icons more and more, both in churches and for personal devotion, it can be for reasons of reverence, piety, embellishment, etc, for the Orthodox Church, an icon can be considered as such only when it can be used liturgically, otherwise, it simply does not qualify as a ‘real’ icon. The East has preserved the original significance and use of icons to a point that no Orthodox church anywhere in the world is allowed to start functioning without an iconostasis (screen with icons in front of the sanctuary) while constantly adding the other icons in the sanctuary and on its walls.

Sister Jeana Visel, OSB had made an extensive research on the subject which she combined with her own icon practice as a student. Catholic herself, she is the right person to talk about the issue of icons in the West, which she does so well in her much needed and important book: Icons in the Western Church:

‘Icons are not simply art like other religious art. It will take ongoing catechesis for the majority of Catholics to gain an understanding of what icons actually are and in appreciation of their sacramental nature. In the face of an age of mass-produced prints, increasing general access to high quality original icons will help convey the power of these images. Those responsible for arranging worship spaces likewise can help increase comfort with icons by designing spatial contexts that will suggest how best to interact with them. Although icons properly require a particular kind of reverence, and sensitive use is warranted, they can find place in Catholic churches among a diversity of other sacred art. Whether used for liturgical, devotional, or historical purposes, icons have a role to play in making the spiritual world visible.

‘Ultimately, it is the transcendence of the icon that enables it to be “intuitively ecumenical”, as Mahmoud Zibawi puts it.’

This introduction had to be made as the West and East differ in their depictions of the Resurrection.

The ever-so appealing Italian and Northern Renaissance and late Gothic representations, have left us a great culturally and artistically rich legacy. Come Easter, the Catholic Church would use some of the imagery of the great masters from those periods. Most of those images are varied reiterations of Christ rising out of the tomb victoriously/triumphantly or hovering just above it and among these we can find supreme gems such as the renditions of 15th century work of Piero della Francesca (proclaimed ‘the best picture in the world’ by Aldous Huxley in 1925) or even more luminous and otherworldly, spectacular painting by Matthias Grunewald from his famous Issenheim’s Altarpiece, 16th century, along with always extraordinary Fra Angelico’s works and a number of other dazzling masterpieces.

REDEMPTION OF HUMANITY

REDEMPTION OF HUMANITY

The icons of the East primarily focus on the Descent into Hell or Harrowing the Hell and the

Myrrh Bearing Women by the Tomb, when it comes to the depiction of the Resurrection. As we know, generally speaking, the event or phenomenon of overcoming Death was known in various civilisations preceding Christianity, to mention but ancient Egypt and Greece here. The Redemption of the whole humanity, however, is immanent to Christianity.

Says Father Michel Quenot, an Orthodox priest based in Switzerland who, after writing numerous books on icons, is one of the highest authorities on icons:

‘As the last stage of Christ’s abasement, the descent into Hell marks the ultimate phase of His humiliation, which simultaneously initiates the ascent of humanity in His wake.

‘In the early church, we should remember, a Christian was referred to as Aphoberos Thanatou (one who does not fear death).’

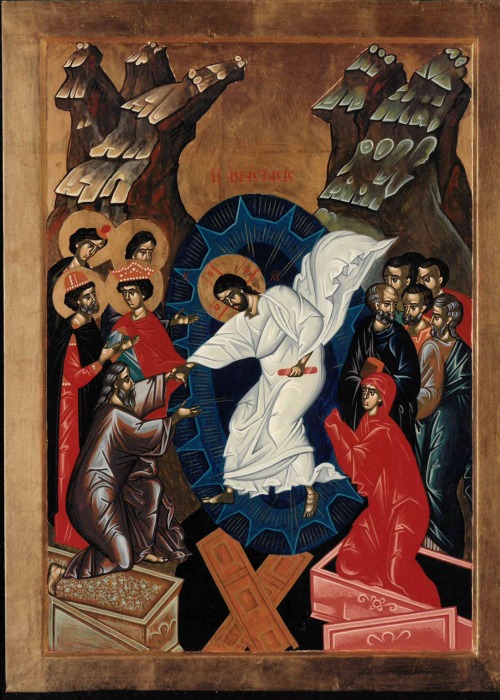

The icon of Christ’s Descent into Hell is also knowN as Anastasis. Dionysius of Fourna gives us the formulae for this particular icon:

‘Hell, like a dark cave, under the mountain. Radiant angels bind Beelzebubb, the chief of darkness; they strike some demons and pursue others armed with spears. Naked and fettered, several men raise their eyes. Many broken locks. The doors of Hell are knocked down; Christ is trampling them.

The Saviour takes Adam with His right hand and Eve with His left. On the Saviour’s left, the kings with crowns and halos. On the left, the prophets Jonah, Isaiah and Jeremiah; the righteous Abel and many others have halos. All around, a brilliant light and a multitude of angels (Guide to painting, Paris, 1845).

‘Death and Resurrection form a single reality through the death of Jesus, since the New Adam vanquished the death that the first Adam had brought upon himself. As “true God and true man”, Christ fully assumes and refashions our human condition.’

As we saw, the East chooses to depict Christ’s Resurrection through Him saving others, or, rather, the whole of humanity. Michel Quenot further tells us that depictions of Christ coming directly out of the tomb are deflective in at least three ways”

First of all, when the angel comes to roll away the stone it is not so that Christ might come out, but rather to show that the tomb is empty. Furthermore, Christ would not be coming out of the tomb since, having descended into hell, He ascends to the Father, followed by the captives He has freed.

Finally, the soldiers are struck with fear at the sight of the angel and not of a Risen One. Could they have otherwise accepted to spread the lie that the body had been removed by thieves? Thus, when the centurion, Longinus, and his soldiers that were present at Golgotha, “saw the earthquake and what took place, they were filled with awe, and said, “Truly, this was the Son of God” (Mt 27:54).

The Myrrh Bearing Women is the most ancient depiction of Pascha, first appearing in a fresco of Dura Europos in Syria, approximately dating back to the year 230 CE. Unlike the Resurrection icon, this one is strictly based on the Gospels’ story, having Mary Magdalene, and Mary, the mother of James and Salome, as well as Mother of Jesus, although not mentioned in the Gospel accounts.

The tradition has the three women with the jars of myrrh and herbs who all visiting the tomb of Christ come across one (Matthew and Mark) or two angels (Luke and John) with one or both outstretched wings pointing to the empty tomb with only a shroud and rolled up napkin/headcover.

Says Michel Quenot: ‘To be sure, the empty tomb is not a sufficient in itself to justify faith in the Resurrection. Had the body of Jesus of Nazareth been found, everything would have fallen apart. The empty tomb is an invitation to seek the living Christ elsewhere, it is a reminder of the angel’s words: “He is risen as he said” (Mt 28:6). The Scriptures have been confirmed and enlightened by the light of the tomb that reveals their meaning. Hence the insistence, at the very heart of the liturgy, on eliminating every trace of doubt’...

FIGURE OF CHRIST

FIGURE OF CHRIST

This scene can also include the figure of Christ in the background more silhouetted than in other depictions. The further profound symbolism includes the dark cave in the background, often of the same shape as the cave where Christ was born and presented as a swaddled baby in the Nativity icon. It is repeated in the neatly spread shroud and a napkin in The Myrrh Bearing Women icon.

The Raising or Resuscitating of Lazarus is another powerful icon which alludes to the Resurrection of Christ by showing Jesus bringing Lazarus back to life after four days.

The icon gives the details of the miracle witnessed by a multitude of people. Christ is in the foreground on one side with Martha and Mary at His feet and the apostles behind, on the other, Lazarus and the Jews who are crowded behind the tomb.

A man rolls aside the stone closing the tomb thus indicating that Lazarus could not have come out by himself. All-bound with grave-cloths, much like a swaddled baby Jesus from the Nativity icon, Lazarus appears at the mouth of the cave, sometimes depicted as coming out of sarcophagus within that cave or outside of it. The stench of the body dead for four days causes those close by to cover their nose and mouth with their clothes. Majestic Christ says: ‘Unbind him and let him go!’ and another important miracle is unfolding before our eyes.

The scene of Jonah freed from the belly of a behemoth/giant fish/whale is not, strictly speaking, a representation of the Resurrection; yet it prefigures it as only the Old Testament could.

Michael Galovic’s art works include traditional icons, contemporary religious and non religious art. See YouTube: Michael Galovic for more.

Images: Top: Anastasis or Descent into Hell, 1996.

Centre: From the Dodekaorton icon: Raising Lazarus, 2020

Bottom: Prophet Jonah, 2020; The Resurrection, 2020.

All icons in this article are by the author Michael Galovic