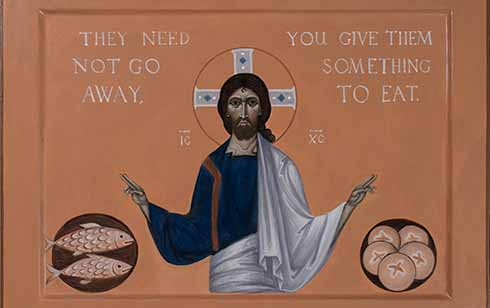

Good iconography keeps you still, drawn to the image and meditating on it.

Good iconography keeps you still, drawn to the image and meditating on it.

Russian artist Philip Davydov is humble, almost dismissive, about the beauty and mystery he creates around the world.

He can spend chunks of his life making, or ‘writing’ an icon for a Church wall and then ’hand it over’ to the community that he hopes will look at it and focus on it in prayer and meditation.

‘The icon isn’t about me and it isn’t a personal expression of my faith. The icon I make is about the congregation or community who will look at it, the people who will be drawn to the image in prayer,” he said.

ICONOGRAPHY RENAISSANCE

Philip, a renowned iconographer, spent several weeks at Australian Catholic University in Melbourne over the summer running icon-painting workshops. Students learned how to create icons of Mary and how to draw or paint Crucifixions. It was one stop in a busy international teaching schedule that reflects a renaissance in iconography worldwide.

Many of his students have attended previous Australian workshops over the years since he first taught here in 2007, usually accompanied by his wife and fellow artist, Olga Shalamova. Students are not accepted or rejected according to their faith, though Philip believes it is much easier for a Christian to write an icon than it is for an atheist. To do justice to an icon is to ‘understand both the art and the theology’, Philip said.

Philip learned his art from his father, Andrei, who was an iconographer and Russian Orthodox Christian priest in the 1980s, during a time of great change in their country. Andrei was one of the first Russian artists to become interested in icon painting after the fall of Communism.

BETTER UNDERSTANDING

Philip is confident the value and importance of icons is now better understood. ‘I make an icon on behalf of the whole congregation, giving the people a focus point. An icon should give the person no desire to move from it for a long time because they are not distracted,’ Philip said.

It’s one of the great differences between icons and Western religious art, which can demand much from the observer and often prompts an inner conversation about the realness, or not, of the images on the canvas. Western religious art often draws the observer from the sacred to the secular.

‘Western art wants to explore a certain idea, to look at the historical background and to stimulate the imagination. The goal of an icon is to focus your mind, to stay and meditate with that image. The task is very different, in fact an icon is to achieve the opposite of Western religious art.

‘Western art painting is trying to render reality. For example, if you see a painting of John the Baptist you start to think if he really looked that way, or is that what his nose was like or his hair. But iconography doesn’t care about his nose in that way and an icon should just give an idea of a human being with features. Clothes worn by the figure in the icon should remind us of garments, but the garments should not distract us,’ he said.

FAVOURITE ICON

One of Philip’s favourite icons is Christ the Saviour (Pantocrator), a 6th-century encaustic icon from Saint Catherine’s Monastery in Mount Sinai, which is considered one of the oldest Christian icons.

‘It is really deep, beautiful and great at the same time,’ he said.

Philip’s not sure what’s driving the revival in iconography, which both pleases and disturbs him. He recently looked at workshops around the world with the idea of participating in one; but gave up disappointed in the quality of what was on offer.

Many iconographers, Philip said, are ‘adjusting’ to the growing demand by priests and others in the art community to produce large numbers of icons. ‘They learn to produce icons formally, making them nice and lovely with a lots of gold, but not even daring to think of an icon as a message, as a living sermon about God. So sad, that it’s this approach, which is promoted and taught, and it is easy to understand – it’s much easier to teach (and evaluate) craft, than to teach theology to be expressed through art.’

RICH TRADITION

Students at ACU were offered something altogether different, influenced by Philip’s rich tradition and their passion for technique and theology.

‘In our workshops we explain the icon and how it can function, we give it visual and religious grammar. We are introducing students to a traditional method of painting.

Of course, we teach students about the anatomy of an image, head shapes, tones, colours and pigments,’ Philip said. ‘But that isn’t all that is involved in writing an icon. What makes the icons powerful is the spirit.

‘The old icons we see in museums are great works of theology, embodied visually. So, it’s the sincerity and power of art, which allow them to be what they are – convincing testimonies of faith and tools for prayer.

‘In medieval time we see many provincial icons with low level of artistic skills, but they are never formal. They have something important to transmit, to say.’

To see some of Philip and Olga’s work go to: www.sacredmurals.com