I am a high-school teacher. Every summer, we take a group of incoming student leaders away for a few days. As part of the experience, some of us rise at 5am to go to Mass at Tarrawarra, a Cistercian monastery in the Yarra Valley outside Melbourne, where a community of monks lives in almost complete silence, pursuing a lifestyle that has not changed much since the 11th century.

I am a high-school teacher. Every summer, we take a group of incoming student leaders away for a few days. As part of the experience, some of us rise at 5am to go to Mass at Tarrawarra, a Cistercian monastery in the Yarra Valley outside Melbourne, where a community of monks lives in almost complete silence, pursuing a lifestyle that has not changed much since the 11th century.

Young people find this commitment utterly confronting. So do the teachers. We tend to use rather a lot of words. The monks follow The Rule of St Benedict, written in the 6th century, one of the more wise and humane works in Western history. It begins with the invitation to ‘listen to a brother who is older than you and who loves you.’ Indeed, listening is the only hard and fast instruction in the whole rule and St Benedict asks his followers to pray Psalm 94 every day, ‘if today you hear his voice, harden not your hearts.’

Hard to argue with someone who never speaks

A friend of mine, Brother Bernie, is the prior of Tarrawarra. He has lived there for about 40 years and is one of the most sane people I know. I tell my students that Bernie is one of the few friends with whom I have never argued. That is because he so seldom speaks.

He describes the monastery as a ‘fridge magnet,’ something that reminds the rest of the world that it doesn’t have as much to say as it thinks it might. Bernie believes that God doesn’t use many words either. The life of the monks involves listening to deep silence.

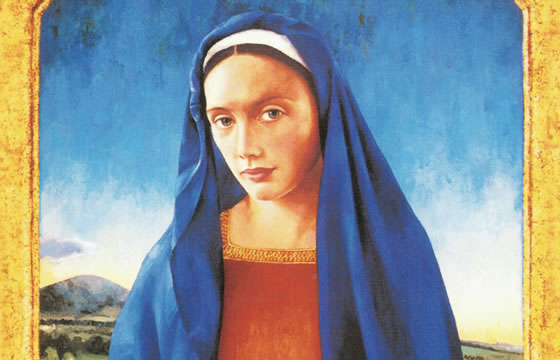

At the back of the church where the monks gather several times every day is a picture called Our Lady of Tarrawarra, painted by Penelope Long in 2000. It is an imposing and thought-provoking image. This may be just as well because the community spends a great deal of time in its presence. It is the kind of picture that may seem straight-forward at first but, after a while, it starts to ask us questions.

Religious art frees us from one-line answers

Great religious art shares this facility. It tends not to be static, nor confined to a single interpretation. Religious art is not created to provide one-line answers but to free us from them. Our Lady of Tarrawarra features the rolling hills of the Yarra Valley in the background, just as there is a landscape in the background of such paintings as Leonardo’s famous ‘Mona Lisa’. This reminds us that we all belong in some specific place.

Mary Mackillop said, ‘there where you are, you will find God.’ There is comfort and reassurance in this. The Lord finds us in whatever place we may be, even if it is a place where we are trying to hide. We could all imagine an image of Jesus or Mary with our kitchens, bedrooms, bathrooms, garages, supermarkets, offices, gyms, schools or hospitals painted in the background. The reality of God is part of our here and now. None of us is forgotten, even in the noisy rush of modern living, a clamour which the monastery helps us keep in perspective.

In the picture, Mary is holding a book in her right hand but she is not looking at it. Could this be the Rule of St Benedict? Or the Bible? Or a book of Psalms? We have to imagine the answer. The Psalms are central in the life of the community as the monks recite all 150 Psalms every week. Br Bernie says that the Psalms are like old friends. Their mood can seem to change for him from one month to the next.

The Lord is present in scripture

Mary’s left hand is open, welcoming and, above all, empty. It balances the hand that holds the book, implying two sides to our encounter with God. One reminds us that we meet God through our rich tradition. The Lord is present in scripture, represented by the book. The other encounter is simply as ourselves, people who come to the Lord with open hands and open hearts, ready for surprises.

For all that, the look on Mary’s face is the heart of the image. It is warm but also challenging; it is not the face of a compliant person but of a figure of strength and independence. It is hard to tell if she is looking up from the book to grab our attention, or if she is grabbing our attention before she takes us to the book. This ambiguity is great. It implies that she wants us to bring our life to all that the book represents. At the same time, we can take so much from the book to our lives. Mary knew more about the meaning of relationship with God than anyone.

The image of Our Lady of Tarrawarra suggests that there are two sides to any relationship. God is completely open to us. He also asks us to be open to him.

Michael McGirr is the author of many books including Ideas to Save Your Life (Nov 2021). Books That Saved My Life, Snooze: the Lost art of sleep, Bypass; The story of a road and Things You Get For Free. His religious books include Finding God’s Traces and Doorways into Hope and Joy at Advent and Christmas. He has much experience as a secondary teacher in the realm of Faith and Mission and currently works for Caritas Australia. He lives in Melbourne with Jenny and their three children.