The Story of Barak

The Story of Barak

The Spirit of Light and Truth

will always be my guide.

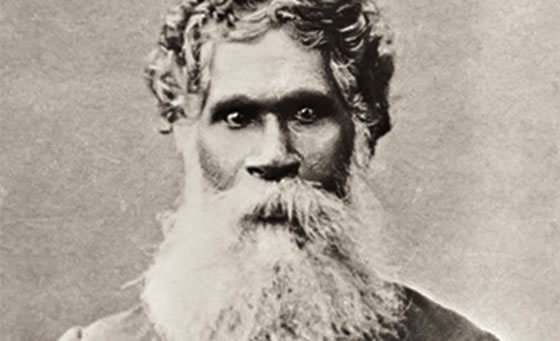

William Barak was born around 1824, becoming the last chief of the Yarra Yarra Tribe. He was often called ‘King William’, or ‘Beruk’ (meaning white grub in a gum tree, and he belonged to the Wurundjeri-willam people. Their country lay along the Yarra and Plenty Rivers.

Barak spent his childhood in the traditional Aboriginal way. However, through tribal dislocation because of Melbourne’s early white settlement, he did not undergo proper cultural initiation. In a brief ceremony, his relations invested him with a possum-skin cloak, a necklet and waist string, and the nose-peg of manhood. Most tribal lore he picked up informally.

Barak received a brief taste of education at the Rev. G. Langhorne’s mission school. While he adapted his own life to the changing conditions, he maintained a remarkably balanced tie with his own culture. He became an accomplished painter in ochre and charcoal and had a strong baritone voice.

In the late 1870s, when Aboriginal affairs came under vigorous public criticism, Barak emerged as its Aboriginal spokesman. He became the acknowledged leader at Coranderrk, the Aboriginal reserve set up in 1863, and was a liaison between officialdom of the colonists and his own culture. He participated in the government enquiry in 1881, submitting a plan for autonomous communities under first manager John Green.

‘Give us this ground and let us manage it ourselves … with no one over us … We will show this country we can work and make it pay. I know it will and we can do it.’ But officialdom did not share his faith. His scheme was never fostered although the land at Coranderrk was retained. Surely his was an Aboriginal voice crying out in the wilderness. Aboriginal voices are still crying out more than 200 years later.

Barak’s father, the old chief Jerrum Jerrum, was buried in the vicinity of Studley Park, Kew, and when he died, the wattles were in full bloom all along the Yarra River. Every year Barak would visit his grave on the anniversary of his father’s death.

Barak died on 15 August 1903. He was in his eightieth year, tired and ailing—and, as he had once prophesied, he too would die as his father had, when the wattles were in full bloom.

Those who knew Barak unanimously described him as a remarkably wise and dignified Aboriginal spokesman, often depicted as erect and bearded, wearing sandshoes and a long coat, a boomerang in one hand and a Bible in the other. I hope the church, who had offered his people the Gospel of Justice in those times, continues to do so in this contemporary, more enlightened age.

The death of Barak was a sad loss to his non-Aboriginal friend, Anne Bon, after so many years of close friendship. She kept her place on the Aboriginal Protection Board and continued to battle for the welfare of the declining population of the Aboriginal people.

This strong Aboriginal man, William Barak, responded to the Christian missionaries of his time and was gifted with the Spirit of Light and Truth. He spread peace and good will with all he met. His strong, simple trust in the Bible, which he always carried with him along with his boomerang, symbolised that his Christian faith and culture had become as one. William became one also with his father, Jerrum Jerrum, as he entered their Dreaming place at that special time when the ‘wattles were in full bloom’.

When the wattles bloom

Dark children are now coming home,

They hold a friendly hand.

A million friendly voices call

Across the crimson land.

There is a ring of brighter hope

Around the wintry moon,

So tell the children they will smile

When the wattles bloom.

The rocky road was far too long

The shadows were too deep,

But they will sing a morning song

With dancing in their feet.

For there is a ring of shining hope

Around the wintry moon

So tell the children they will sing

When the wattles bloom.

Their lonely fire was flickering low,

their Sacred Dream was dim …

But there is a brilliant ring of hope

Around the silvery moon

So tell the children they will dance

When the wattles bloom.

R. Cameron, 199